Write a scientific paper:

4 essential tips

You have been working your butt off in the lab for months or even years, and now you (or your boss) have decided to publish your work. It is time to sit down and pull everything together into one document that you will put out to the world. A formidable task. To help you, we have gathered some thoughts and advice from various specialists to provide you with four essential tips for writing a scientific paper well.

Hopefully, this will not come a surprise to you: writing research papers is an obligation for scientists. Whether you feel the pressure of “publish or perish” or not, publications mean grants, tenures, and funding – to name a few. Moreover, above the “career” stuff, scientific papers are your window to the rest of the scientific community.

Scientific research is about learning something new about the universe (or multi-verse) that we never knew before. A scientific article is your opportunity to share that story with the scientific community. However, many researchers find it tough to actually get their science down onto the page. That is why we have pulled together our four top ideas to help you write your scientific article more easily.

1/ To plan, or not to plan

First things first, you need to know what content you will be putting in your paper. Journals vary slightly in structure and the length of the articles they accept. But you should expect to write the following:

• Title,

• Abstract,

• Introduction,

• Materials/methods,

• Results,

• Discussion (and/or conclusion).

The order of these elements in your paper will depend on the journal. Some will expect you to include a detailed methods section in the body of the paper, whereas others (such as Nature) will have you summarize them at the end.

There are always huge amounts of information to include. Yet a paper is much more concise than when you write a PhD, for example. So, it is essential to go in with some kind of plan. How you chose to make your plan, however, is up to you. Some authors prefer to meticulously define every single step of their paper before writing, whereas others will have nothing more than a rough outline. In reality, most pre-planning lies somewhere in between.

Public engagement specialist, Dr. Emily Burns, advises that you should “build a framework for the scientific paper first, rather than diving right in.” You need to think before you write if you want to provide a logical account of the facts associated with your research. She says, “Planning out each section with the key points and figures for each will help you to find your narrative at the start – rather than ten hours in!” In short if you know where you are going, then it’s much easier to get there.

Whatever the case, know that any time spent on a plan is never a waste. Fiction writer, Randy Ingermanson says that at least a loose plan is crucial. He refers to what he calls “the Snowflake Method”. It denotes the process of building a straightforward plan or outline whilst still leaving enough breathing room for your text to evolve as you write. Even though he describes this method in the context of fiction novels, the same applies to scientific writing too – many of the best ideas come out when the pen hits the paper!

2/ Target your readers

The goal of your scientific paper is not only to publish your results. Surely, you want other researchers to actually read the paper and, ideally, do something with the information in it. This means that your writing needs to be clear enough for other scientists to understand the context of your work, what you did and your interpretation of the results. Paper writing is as much a communication exercise as it is a research one.

You are addressing experts. This means giving the necessary information to understand your research without explaining the entire back-story. You can break your readership down into the types of researchers you think will be interested. If your research is in an interdisciplinary field, such as a cross-over between physics and psychiatry, your readers will need you to be more forgiving with the technical details than if your journal has a more specific audience.

Eric, a trainer in written communication at Agent Majeur argues that you should always give more explanation than you think an expert would need. He says, “on one hand experts won’t be mad to read good explanations of things they already know. On the other, many of them will not be experts in your precise topic so your article must help them to understand.”

The objective is also to tell the scientific community what you think those results mean, based on the knowledge that you have thus far. To do this requires two vital features; (1) the limitations of your study; and (2) why yours and previous data lead you to your conclusion. These key components of the discussion need to be as clear as your methods and results, and that is where lots of people slip up. Take your time to map them out with your co-authors before writing and, later, be particularly critical of these in your edits.

3/ Beat writers block

We have all found ourselves woefully staring a blank empty page at some point, unable to get our thoughts out. Unfortunately, however, there is no easy solution to overcome this frustrating feeling, known as writer’s block. James, a trainer at Agent Majeur explains that “you need enough mental space to be able to write. The words won’t come out if you have too much on your mind.” Try getting some small tasks done that are easy to cross off your to-do list or maybe going out for a socially distanced walk. His personal technique is, “to tidy up my workspace, or weirdly the kitchen if I’m at home. It clears my head before writing.”

If you are still struggling, then you could try a method known as “free writing”. The concept is simple: set yourself a block of time between 10-20 minutes. Pick a section of your scientific paper. Then, during the time you’ve set, your sole objective is to write as much as possible about that one thing. Don’t worry about spelling mistakes, sentence structure or other style points. Just write as much as you can, avoiding any distractions shy of a fire in the building. Then, once you reach the end, stop. Get up and give yourself a break away from your work. Once you’re ready you can then go back and edit your piece. The main objective is to simply get the ideas out of your head without judgement.

4/ Know how to edit

Once your ideas are down on a page, then comes the editing. Internationally acclaimed author, Roald Dahl, was quoted as saying “Good writing is essentially rewriting.” Unsurprisingly, he isn’t the only one. There are so many other authors and writers who have made almost identical statements that it is impossible to know who said it first. Moreover, it is a consensus that can not only guide us as writes, but it serves to reassure us too. Your first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, it shouldn’t be perfect. Only the final version is the one your readers will see.

Often, people find editing a very hard task because they don’t know what to look out for. Nobody expects you to write like Charles Dickens. In scientific papers, your main objective is to be understood. That means the simpler the writing, the more effective it is. An easy way to simplify your writing is to shorten sentences. Be strict: one idea per sentence. Go back through your draft and force yourself to shorten any sentence over 15 words. You will find it helps.

Also, challenge the language you use. Underline every word with four syllables. Can you replace them with less technical terms? Nobody is suggesting that you replace specific terms related to your research. But by using simpler words around that technical jargon, it helps make the writing slicker.

To conclude, writing a scientific paper is more than just bundling together a few results. The best papers are from authors who think about what the message of their article is and how they express their research in the words they use. A truly good paper is one that reads well. Bear in mind that the process is often long, and it is OK to take it step by step.

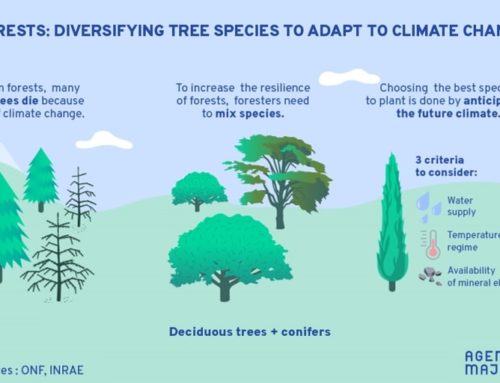

For more on how to illustrate your paper, read our article about science illustration here.

> Written communication

27/08/2020