Scientific writing

Michael Alley, author of ‘The Craft of Scientific Writing’, published by Springer, is a professor at Penn State University (USA). Initially a physicist, he has been working for 20 years in the field of scientific and technical communication.

Agent Majeur: In what way is scientific writing specific?

Michael Alley: With scientific writing there are specific challenges. When we write, we should be sensitive to what the audience is capable of understanding. But we must also understand why the readers read our work and why they are important to them. We are often led to write on very specific subjects. Our readers may be scientific specialists in that field. In this case, their background allows them to understand the subject, they know the vocabulary. Generally, these writings also address scientists from other disciplines or the general public. Those readers do not have this level of knowledge. For example, when a scientist writes about a turbine blade cooling system, many people do not understand what it is about, why it is important, where it takes place and what the stakes are. And this complicates things for the writer.

What are the goals of a scientific document?

There may be two distinct goals: to inform or to convince the readers. The scientists are not always aware of that. And the style to adopt is different according to the goal. A purely informative document – for example, assembling instructions – is often built from lists of actions to perform. In general they are numbered. Each element of this list will include one or two sentences. The paragraphs are very short. Conversely, this style is not acceptable for a document written to convince – for example, a commercial proposal. Paragraphs are longer. Most of the time, a document is used both to inform and to convince. Scientists must therefore mix both styles: the ‘list’ style and the ‘comprehensive paragraph’ style.

How would you qualify a good title for a scientific document?

I often ask this same question to the scientists I’m in close contact with. And their answer is often: short and pleasant. This is probably something they have learned in a writing training course they took a long time ago. But this does not apply, for example, to the title of a scientific article in a journal for researchers.

In this case, the title must allow the reader to:

– identify the subject of the study / the scientific field

– differentiate this document from all the other ones on this subject.

In the book, I give the example of a title: ‘The effect of humidity on avalanche growth’. A reader may imagine it is about avalanches as the ones that occur in the Alps. But, in reality, the document is about electron avalanches. This title does not help identify the subject of the article. In general, when writing an article, the title is written at the beginning. Then, at the end, it is reworked to make sure it meets both objectives.

Discover more tips by trying to answer the following questions in our scientific writing quiz:

1. What is the best way to highlight detail in text?

A – link

B – illustration

C – position

D – repetition

2. What is the right length for a paragraph?

A – 6 lines

B – 11 lines

C – 15 lines

D – there is no ‘right’ length

3. An illustration is referred to in the text:

A – before its occurrence

B – after its occurrence

C – never

Answers from the book “The craft of scientific writing”:

1 : B, C and D.

2 : B – except in a purely informative text, a paragraph should be between 7 and 14 lines.

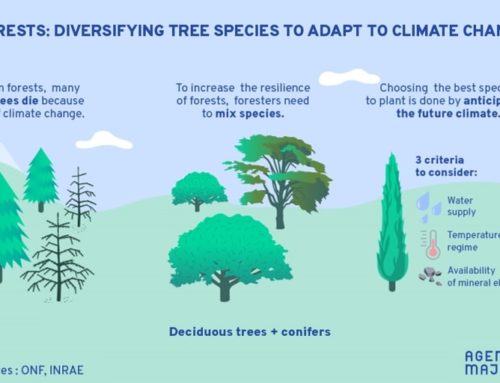

3 : A – in an informative document, an illustration should be numbered and referred to before its occurrence.