The 6C’s of science popularisation

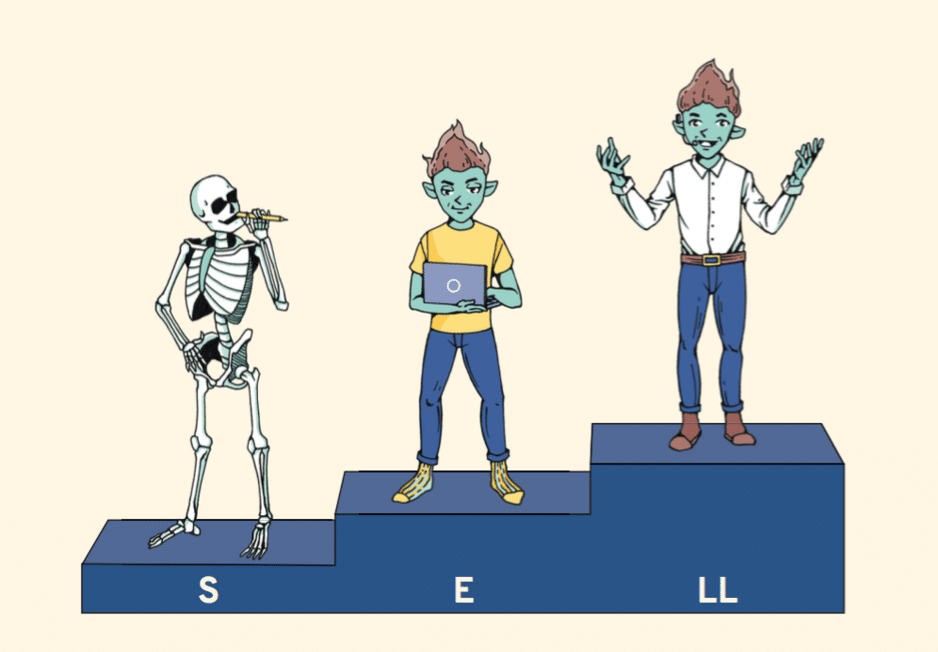

It is well known, as a communicator, you must adapt to your public. And when the audience does not have your level of knowledge, you need to make your content more accessible – or “popularise” it. In the words of the famous geneticist, Albert Jacquard: “French people seem to wrongly think, ‘No one understands me, so I must be more intelligent than other people’. I think that, on the contrary, we must say, ‘If no one understands me, then I didn’t explain myself very well”. To express yourself better, here are the essential ingredients: the 6C’s of science popularisation created by Agent Majeur.

To popularise is to make complex ideas simple. It is a difficult exercise, because it requires taking a step back from your expertise. Assessing the level of knowledge of your audience is not always easy either. In science popularisation, some speakers call this the “curse of knowledge”. Basically, this means that a person who knows a subject well will find it difficult to explain themselves to a lay person. A speaker or writer overestimates how familiar the audience will be with the topic at hand, misjudging their ability to understand. But, how far should we go in terms of simplification?

In our experience, particularly through our training courses in popularisation, we learnt the following: communicators rarely over-simplify. In fact, they generally don’t even realise how far away their level of expertise is from that of their public. In oral communication, the result can be seen by the tired – even sleeping – faces of the audience. In written form, reports and other documents that are too technical will end up in the waste paper bin.

Since all of us write to be read and speak to be heard, our team brought together proven techniques under the name « the 6C’s of science popularization »: Clarity, Connection, Context, Concreteness, Color and Conversation. Follow our guide !

1. Focus on clarity and define the words you use

Clarity is a prerequisite for any undertaking in science popularisation. Therefore, when speaking to an audience which isn’t as familiar as we are on a given subject, it is important to watch out for jargon. These are words very commonly used between experts in the same field, but unknown or misunderstood by non-specialists.

To make these words intelligible, our advice is to use the funnel technique. Start by using simple and general words and progressively make your way to complicated and specialized vocabulary. For example, to define basalt, volcanologist Jacques-Marie Bardintzeff’s suggestion is to proceed step-by-step. Begin by a generic definition easily understood by everyone: « it is a black volcanic rock ». Then, progressively turn to more complex explanations, describe how basalt is formed or its composition. Imagine that you are speaking with a person that does not share the same native language as you. Focus on simple words and sentences, and explanations that are easy to grasp.

Furthermore, when you become involved in science popularisation, beware of acronyms. If you can avoid using them, do not hesitate to replace them with common words which will be easier to understand by your audience. If not, define them. To avoid confusion, explain the meaning of each of the letters in an acronym. Indeed, many acronyms can have different meanings depending on the field in which they are used. For example, in biology, PCR is the contraction of « Polymerase Chain Reaction », a technique used to amplify DNA sequences. But this acronym can also refer to the Plan Control Room in a factory, or a Performance and Cost Report in the field of management.

Finally, we are often tempted to list several elements to organize and clarify our speech. But an audience can only remember a list of two or three elements, nothing beyond four. When you have many aspects to discuss, divide your speech in three or four parts which include subparts. This structure will be clearer for your audience. It will make it easier for your public to memorise key points.

2. Create a connection with your audience

Our emotions play a very big part in our decisions and reactions. It is interesting to use them in science popularisation to create a connection with the audience. You can, for example, try to surprise your audience, make people laugh, astonish or even scare them. When you want them to reach a decision and take action in a field linked to health or safety, fear is strongly recommended. For example, you can communicate on the consequences of a possible accident, in the event of non-compliance of the regulations. On a more cheerful note, entertaining and amusing your audience is always an excellent way to bond with people.

To create a connection, you can also share your own emotions. Tell your audience what drives you in your work, or what you find enjoyable. Enthusiasm, much like laughter, is infectious. And do not hesitate to share personal anecdotes. For example, tell the challenges you faced or the accomplishments you are proud of, or other highlights in your life. All these stories will make you more humane and spark the interest of your audience. But beware not to make your presentation revolve around you! In the words of Seneca, “anything done to excess is a vice”.

3. Place your work in its context

The context of your work needs to be clarified when you carry out science popularisation activities. You need to shed light on the scientific, social, economic or even cultural issues in your field. Let us take a health-related example. A researcher has produced a prosthetic limb with integrated electronic sensors. The innovation allows a patient to collect data about the condition of the prosthetic on their own, from home. The scientist, to help us better understand the importance of their innovation, would benefit from telling us how many patients could be helped each year and the financial savings that a design like this would make to the social security budget.

Your audience won’t always be aware of the proximity between their own problems and your scientific research. So perhaps you could explain several applications that affect their daily life: right now, in the near future or 10 years down the line. Imagine that you must give a speech to popularise data backup in front of an audience of business executives. You can start your speech by asking, “Who among you saw their company impacted by the fire of the OVH data center in March 2021?”. Considering that more than 3.5 million web sites were affected by this disaster, members of your audience are likely to raise their hand. Give them time to do so, then continue: “Among those of you who were impacted by this fire, who saved their data somewhere else, in addition to using OVH servers?” Once again, give them a moment to express themselves. Your point is made: they now feel concerned by your subject. They are ready to listen to you attentively.

4. Be concrete

When you popularize, avoid abstract speech as much as you can. To stay concrete, bring samples, models or perform demonstrations. It is useful to hand over samples to the public if your audience is not too big. However, when you speak in front of several dozens of persons, you need to avoid this type of tool: when the sample arrives at the 5th or 6th row in the room, you have already moved on to another aspect of your subject. You can also draw on the 5 senses of your audience, by giving objects for them to see, to hear, to taste or to feel. They will remember your explanations better.

Another way you can be concrete is to illustrate your speech with examples: “composite materials increase the performance of athletes. Skiers, for example, see their sliding speed increase by 4% each year.” Moreover, when you mention figures, it is interesting to link them to notions that appeal to your audience. In science popularisation, cubic meters are often converted to the number of Olympic-size swimming pools. In the same way, small objects are often compared to the diameter of a strand of hair. For example, “6 times light speed” is easier to understand than “1798754748 m/s”. Or for instance: “Nanotechnology is defined according to spatial scale, meaning the nanometer or the billionth of a meter. It is very small. A sheet of paper is 100 000 nanometers thick.”

Based on this principle, do not hesitate to create your own original comparisons. You know that trees absorb CO2 in the atmosphere thanks to photosynthesis. To communicate the importance of this phenomenon, here is an example of the comparison used by the Office National des Forêts (French National Forest Office): a tree can absorb 5 tons of CO2, or the equivalent of 5 round trips between Paris and New-York. By using these comparisons, your audience can form an image in their mind and grasp what you are saying.

5. Add color to your speech

In science popularisation, it is important to rely on images, literally and figuratively. In the literal sense, images are not limited to photos. There are many ways to show what you work on: graphs, videos, schematics…

In order to be understood at first sight, graphs need to be simplified. A bar graph for example, must only include 5 to 6 data maximum. For photographs and videos, over the course of your work, try to remember to take high-quality pictures (resolution, lighting) or to film the important steps. Schematics, on their hand, are used to show what is not visible to the naked eye, because the element is too small, too big or inaccessible: the center of the Earth or the epidermis, for example.

In the figurative sense, relying on images consists in using analogies, metaphors, phrases that will allow your audience to picture what you are saying, and thus to add color to your speech. An analogy is a resemblance between two or more different concepts. It makes it possible to describe a more complex term to help understanding. It is the case, for example, in this quote by Otto Frisch: “If an atom was blown up to the size of a bus, the nucleus would be the same size as the dot on this i”. A metaphor, on the other hand, consists in using a concrete term to express an abstract notion by analogic substitution, without introducing a formal comparison. For example, “Space is a unique laboratory to study extreme phenomena”. Finally, a phrase is a concise expression, which summarises an ensemble of meanings in an attractive way. “The catholic religion is being replaced by the cathodic religion”.

6. Make conversation

Even though they are no experts, your audience loves to participate, give their opinion. Hence the importance, when you engage in science popularisation, of making conversation, taking the time for question and answer sessions. During a presentation or a workshop with a small group of people, you can give the floor to everyone. For a larger audience, or when you are doing a videoconference, you can use polls. This way, you can collect everyone’s opinion in no time.

In fact, by promoting these types of exchanges, you will realize that you have much to learn from your audience, its questions or reactions. Science popularisation is as enriching for the person listening as it is for the person speaking! Thinking about your research in a different light, pulling it together to explain it better allows you to take a step back. And with this new outlook, you might even explore new paths…

Now, it’s time for you to try. Clarity, Connection, Context, Concreteness, Color and Conversation…Seize the 6C’s of science popularisation created by Agent Majeur and apply them to your own field of expertise. They will give you new ideas to improve the understanding of your speech, whatever your audience.

You can find the 6C’s of science popularisation compiled in 6 videos on our YouTube channel.

> Popularising science

28/06/2022